THE QUEYO ADVENTURE

1947 · 1948

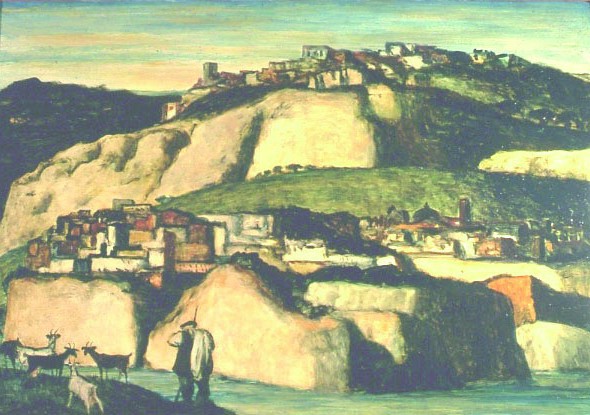

In 1947 in Milan there seemed to be no market for Fiume’s works inspired from the Italian Quattrocento and the metaphysical painting of Giorgio de Chirico, Alberto Savinio, and Carlo Carrà. Clearly, there were elements of novelty in his Cities of statues both in relation with painting and with Fiume’s ideal of a sculptural architecture represented in them, that were not so easy to grasp at first sight. Yet, determined to establish himself in the art community he decided to resort to an original stratagem. He invented the existence of a Spanish gitano painter, gave him the name of Francisco Queyo, and produced a number of works inspired from the Spanish tradition and the gypsy folklore using all his technical ability to carry out a number of paintings that would be easier to understand. He signed them F. Queyo. Then he showed some of those works to the Gussoni Gallery of Milan telling the entirely invented story of the painter Francisco Queyo. He said Queyo was a friend of his, a refugee from the Franco regime, living in Paris, who had asked Fiume to organize an exhibition in Italy for him. The paintings were received with enthusiasm and the exhibition turned out a big success. All the paintings were sold very quickly and an important art critic of the time, Leonardo Borgese, wrote that Queyo was a Spanish master many Italian painters could learn from. However, his friend the writer Dino Buzzati, who was also a painter, recognized his hand, so Fiume revealed he was the author of the paintings signed F. Queyo. And this was the adventurous beginning of his career as a painter.

CRITICAL TEXTS

Precious premise regarding the veracious story of Francisco Queyo

from Francisco Queyo – Salvatore Fiume, Hispanidad

Edizioni Bora, Bologna, 1993

Francisco Queyo, known as a Spanish painter, never existed in flesh and blood. But his paintings, each painted by me, appeared in five or six exhibitions receiving incredible acclaim from public and critics alike. The name Francisco Queyo, who in his catalogues is declared to be that of a gypsy, does not appear on any official public register in the world… In Milano after the war I made the rounds of gallery after gallery, showing my paintings and drawings, without obtaining even the slightest glimmer of attention… The house that I had found in order to be close to the big city, was at Canzo in the Province of Como. The money for the rent I had borrowed from Franco Ottina, an unforgettable Lombard. Up there among the mountains, holed up in an old dilapidated spinning mill rented for a song, I invented a painter. I gave him a story, I painted his paintings, and I baptized him Francisco Queyo: Spanish painter… In 1946 I had still never been to Spain, but I knew it down to the slightest detail by way of an extraordinary book written in the eighteen hundreds by Daviller and illustrated by Gustave Doré, in the wake of a voyage through Spain. The customs and costumes from that time to 1946 had probably changed in the big cities, but certainly in the rest of Spain they must be much as they had been in the time of Daviller’s voyage, by reason of their close resemblance to those of Sicily. Probably some drop of Spanish blood had to have been mixed in distant times with that of Sicily, seeing that, in mine, there boiled the desire to defy bulls in arenas and live the wandering life of gypsies, of whom Doré had left a wealth of sketchings… From the study of these drawings I passed to the painting of Goya, and of that school of the Caravaggio-esque Sixteen Hundreds so widely diffused in the churches of Italy. From Caravaggio I had come away with more than one lesson, as occurs to anyone trying to break into the practice of art; from him came the passion for chiaroscuro and the unexpected splendor of luminosity that leaps out like lightening in a thunderstorm… Everything I needed to know in 1946 in order to bring to life in my laboratory a painter who could excite public and critics, did not come only from the cultural circuits from which I extracted Queyo’s style, but also from a manual ability which had not been in circulation for long time in the work of painters. The invention, as one can see, was not the outcome of a facile improvisation, which in any case would not have been enough in itself to attract the attention of public and critics. What Queyo needed was a story, a “curriculum vitae”. To do this required going from the paintbrush to the pen… I dipped my pen in my own life and in that of a gypsy whom I had once met right after the war while he was putting on a show in the main square of a small town in the Piedmont where I was released from my duties in the army, near Ivrea… With this gentleman I also shared the wandering life I had behind me. Of personages like him, illusionists, three card monty hucksters, fake cripples, professional panhandlers, retired lion tamers, I had known quite a few in Milan, frequenting the bums and hobos in 1936. That’s why our encounter was like that of two colleagues, or better yet, like those who immediately recognize each other as being two chips off the same block… I invited him over to my house to do a drawing of him with the casacca and the rest of the outfit copied from that of the great Grock (pseudonym of Charles Adrien Wettach, 1880-1959, the famous Swiss clown, editor’s note) of whom he was an incredibly able imitator. While drawing him I heard the story of his life, part of which I extrapolated and stuck in that of Francisco Queyo. He told me how at the time of the Republic of Salò his life had been far from easy: he was beaten up by fascists when he tried to do his show in areas under their control because they suspected him of being a partisan, then beaten up again by the partisans suspecting him a fascist spy. Fed up with suffering so many blows, he had gone to work in a factory near Biella where his talents where greatly appreciated as he succeeded equally as electrician, plumber, machinist, bicycle repairman and who knows how many other odd jobs, around the plant and the boss’s home… I gave Francisco Queyo a birthplace: a gypsy wagon under the walls of Avila. I had him travel around Spain for circa thirty years, during which, during his long layovers, I had him cultivate the practice of painting, and had him tell in the first person how he went into museums and churches and alternated the painter’s art with that of acrobat, flying on the trapeze and walking a tightrope strung house to house in small towns where he travelled with the show. But with the outbreak of the civil war in Spain he was beaten up first by one and then by the other of the opposing forces, both sides suspecting him a spy. Weary of being clobbered left and right, he set out across the Pyrenees to come down into France, where “outcasts” were aided and abetted. Now, with the war over, he was living in Paris, from whence his paintings arrived to Italy… Yet this was not sufficient to assure successful sales. It was necessary to organize the exhibitions without revealing the whereabouts of the artist. For the person I chose to present the paintings to galleries, keeping the artist ́s address secret wasn’t difficult; it was enough to tell the dealer it would give rise to competitors. My role was playing the supposed deliveryman of my friend. When the dealers thought I was handling the painting too roughly they became hot under the collar, scolding me to be more careful. The first “Queyo” show took place in Via Manzoni at the Galleria Gussoni in 1948. On opening night my wife and I mingled like church mice unnoticed in the crowd, thunderstruck by the enthusiasm we saw on the faces of the visitors. Usually shows stayed up two weeks with many unsold paintings remaining on the walls. Five days after the opening, the walls at the Gussoni Gallery were bare. Every last painting of Queyo had been sold. The Spaniard ́s success was also celebrated by the press, spreading from the major dailies to the provincial papers. In no time at all Queyo had conquered the market. Galleries all over Italy clamored for shows, and clients were lining up to have their portraits painted. Up to the time Queyo’s success was proclaimed, a foreigner to boot, Italian colleagues had had nothing to say. But once word got out that the paintings had been made by me, the tide of envy stirred a lot of talk in the backrooms of galleries and the studios of my fellow artists. Accusations of fraud, of falsification, of hoax came even to the ears of magistrates, who could take the incident into consultation before having a concrete denunciation… when (in the Sixties) Queyo was at last arraigned before a formal court at the Press Club of Milan, promoted by myself, Dino Buzzati and other friends, the President of the court asked me what I had to say for myself. I replied, “I did not make false paintings of an existing artist, but authentic paintings of an inexistent one”. One hundred and eighty paintings make up the entire production of Francisco Queyo, not one more. After that happy season I found I could no longer paint a single painting with the same style and with the verve that I had brought to Queyo, although long afterward I was asked for his work. At the bottom of this operation… there had been the poverty from which those one hundred and eighty paintings had released me. The first exhibition under my own name drew many who, without the Queyo episode, probably would not have come to see it. The critic Leonardo Borgese, to whom Dino Buzzati and I had revealed the whole story, wrote in the Corriere della Sera a beautiful article for this first real show, regretting, however, that he had let himself be taken in by the figure of Francisco Queyo. I don’t possess a single work from the hand of that painter, and this pains me because I had taken a liking to the fellow. And because, as if I had had nothing to do with his work, I consider him an extraordinary artist. My debut with my real name took place with the paintings in which I began the series of the Islands of Statues and of the Cities of Statues, of which I recorded only one sale – a historical selling for me as the painting was purchased by the director of the Museum of Modern Art of New York, Mr Alfred H. Barr Jr who visited my exhibition while passing through Milan in 1949.