CITIES AND ISLAND OF STATUES

From 1946

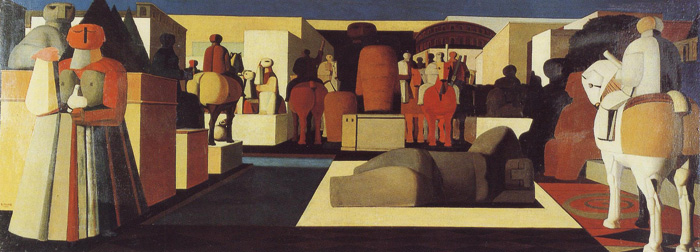

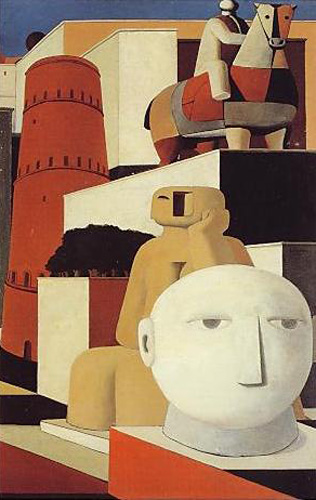

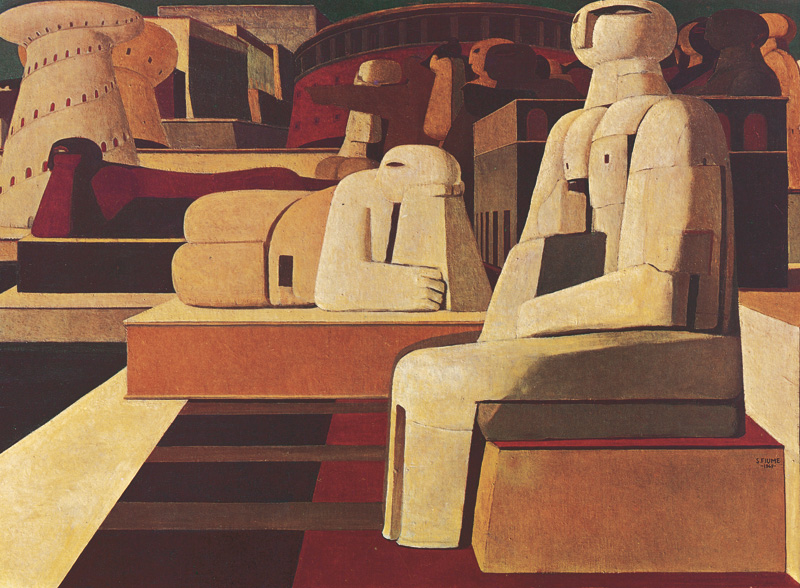

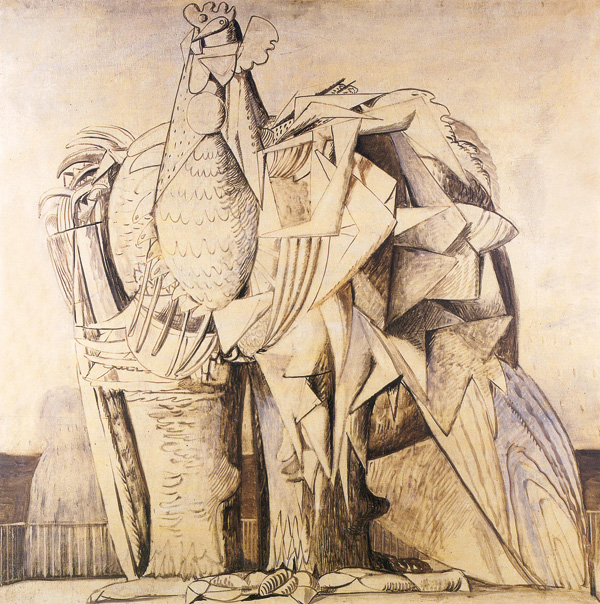

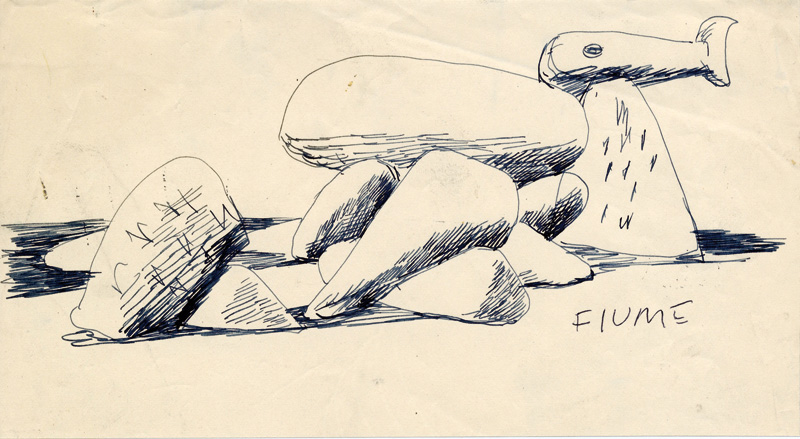

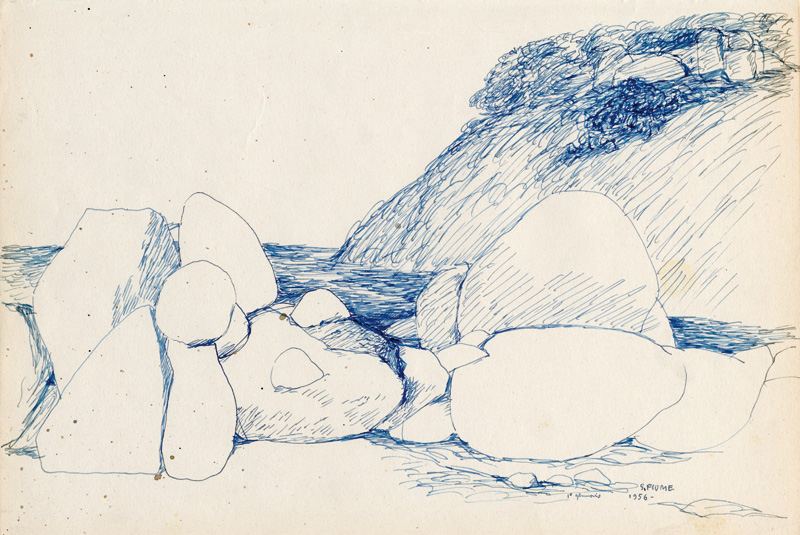

In Fiume’s early paintings of the 1940s and 1950s known as Cities of Statues, the influences of the Italian Renaissance painting and of the metaphysical works of Italian masters like Alberto Savinio, Giorgio de Chirico, and Carlo Carrà are quite evident. Yet, innovative elements in such paintings by Salvatore Fiume had to do not only with the sphere of painting proper, but also with an idea of sculptural architecture. The City of Statues at the MoMA, painted in 1947, is one of the first examples of his research in architecture through painting: an architecture whose buildings are conceived as huge inhabitable sculptures geometrically anthropomorphic or zoomorphic.

CRITICAL TEXTS

…When Fiume talks to you of an island of statues, gigantic inhabitable statues, which he would want someone to let him build, you shouldn’t be amazed or smile as if you thought this was only fantasy. In fact, if no one will not build it for him, he will build it for himself. He is his own patron and he bleeds himself for Fiume and his ideas. What matters to him is that things be done, and quickly. In a sense his painting is an abstraction, more filtered and precious, but the dimensions of his imagination are in the scale of construction. Fiume paints what he would build. You can even walk within his world; islands, heads, domes are all alike. And the analogy originates from the fantastic stories, regal and comic, of his hometown. He is a Sicilian Gaudì…

DINO BUZZATI

from A Renaissance city lies at the bottom of the Ocean

“Corriere della Sera” 16th December, 1956

…Pick up a stone from the road. It will leave you completely indifferent. A stone of the same shape and material enlarged one thousand times would start impressing you. Now try to imagine a stone thirty thousand feet tall. Subjugated, men would stop to contemplate it all day with their heads tilted upwards; tourists, painters, photographers, and poets would come to see it from all corners of the Earth. This is to say that grandiosity alone creates beauty (as well as, on the opposite end an aesthetical emotion can result from smallness, from concentration, and from intimacy. The examples could be endless. Dwarf the Gran Canyon or Mount Cervino down to the size a couple of metres. Shrink the Cheope’s pyramid to the size of a paperweight: what would remain of it? Well, this feeling of largeness as a source of poetry – a feeling that aware or not the old Pharaohs had probably developed in the highest degree – is, if not the main motif, one of the main ones in Salvatore Fiume, painter, engraver, writer, ceramist, stage designer…

ENZO GUALAZZI

from A personal universe

Catalogue of the exhibition at the Tourism Headquarters

Palermo, 1972

…In 1946, Alfred H. Barr Jr. published in New York his fundamental volume Picasso, Fifty Years of His Art. A few months later he was in Europe to observe up close the situation in art that was emerging from the chaos of the war. As in his previous visit of 1935, he had planned to make some acquisitions for the MoMA in New York, of which he was Director of Collections. It was thanks to this post-war reconnaissance that one of the first islands by Fiume was able to go to that museum. It might be too easy to reconstruct the causes of that precocious recognition and could seem superfluous now that Fiume figures among the masters of modern Italian painting. In any case, it is worth remembering that at the time the Sicilian painter was one of the young up and coming artists, and the only one who was visibly working in a typically Italian avant- garde area, metaphysical painting.

ELENA PONTIGGIA

from The City of Statues. Fiume’s metaphysical season (1946 – 1955)

Catalogue of the exhibition Salvatore Fiume, a Nonconformist

of the Twentieth Century, Spazio Oberdan, Milan 2011

Salvatore Fiume is an artist who all know but few know who he really is. Art aficionados remember his name well, yet the image they have of his research is, very often, partial: it is limited to an epoch, if not to a single subject, of his production. The complexity of his work generally escapes one and all, not being only concentrated on painting, but also extending to sculpture, architecture, stage sets. And it particularly escapes the intensive season of his first maturity when Fiume creates an immovable world of statues and totems: a season, corresponding to the first decade after the war years, which has been called…metaphysical. How could it be that a period which is so replete with evocative charm and not missing any acknowledgements paid to the artist (the approval given by poet critics such as Carrieri and Buzzati; his participation in the Venice Biennial of 1950, due to the support given by Savinio; his friendship with Gio Ponti; his activities as a set designer at La Scala in Milan; the purchase by the MoMA of New York of the Città di statue, or City of Statues, then directed by the legendary Alfred Barr) has been ignored, if not forgotten, so much so that in the understanding also of scholars and experts, Fiume’s paintings are identified with a sensual and soft world of odalisques and women’s houses, not with an enigmatic city of statues and marble? There could be varied reasons, even if we do not wish to call up the arbitrariness of every critical fortune (habent sua fata picturae…) or the occurrence of contingent circumstances. There is one, however, which could not be omitted and which we would like here to demonstrate at least summarily. The panorama of Italian art, in the first two decades after the war, has been much of a battlefield between two trends: a more or less expressionist realism and geometric or informal abstractism. While historiography has taken into account these two alignments, it has underestimated (and often fully forgotten) any experimentation which did not form part of them. Yet also, though made up of a very small quantity, those experiments were still being done, starting from a so called mental figuration, away from realism, naturalism and expressionism, and instead linked with a metaphysical lesson drenched with classical memories (whose fathers, among others, were mostly still alive and functioning in those decades: to take just one example, Donghi was deceased in 1963, Campigli and Usellini in 1971, de Chirico himself in 1978). From this general historiographic prejudice…one should not remove Fiume’s actual metaphysical season. Including the aggravating circumstance that, in his case, one could not fully understand the Sicilian, or rather Arab and Middle Eastern, vitality and sensuality of his painting, unless one takes into account that marble chill of forms and figures making up an ensemble of antithesis and premise. All of Fiume’s paintings move between two opposite polarities: on the one hand, a breaking through and uncontainable physicality, on the other a suspension of time and life. His visions of odalisques and Japanese geishas, of bullfights and dreamlike beasts, cannot be fully understood unless one reflects on the origins of that vitality: the omen of an immovable world, of a people made up of characters who, to use de Chirico’s words, “have divested life’s orgasm” and who they lay out on the canvass like chessmen. “The ability to switch off every glimmer of light, of that flowing and explainable light, in the painted pictures, to dress them all over again with that solemnity and that immobility, with a serene and perturbing countenance, like pictures containing the secrets of sleep and death, is the privilege of great arts”, de Chirico wrote yet again in 1920, in a piece which Fiume probably was not aware of, but which he might have well signed…